There are few things cooks covet more than spoons.

It’s an odd notion, outside of context. But at the end of the day every profession has a toolset: a box of things that augment their skills, extend their reach, or grant them superhuman ability. A practitioner must develop trust, familiarity with their tools. And eventually that trust gives way to care, devotion, even a kind of love for these hand extenders and power suits.

You may find yourself asking, but what of the other tools? Why would not certain cooks cling to their pastry brushes, their offset spatulas? Some of the best line cooks I know never set down their pair of tongs, never take a smoke break without securing their knife. Why would these tools not be foremost in the daydreams of the professional chef?

I cannot tell you why. But this I know: across my career I have seen great chefs lament the loss of a misplaced spatula. But I have seen them spit daggers and overturn tables at the loss of a perfect spoon.

A new knife is exciting for a day, this is true. Cooks leave their stations half-prepped, tools clattering behind to huddle around a new blade. But within hours the excitement dies down as the pristine edge begins its work and joins the toolset. Knife-love is fickle, fleeting; its shine dulls with use, and without proper upkeep its razor wit leaves with it, a loss of body and mind.

But in the professional kitchen you will catch sideways glances of unabashed longing from even a seasoned line cook over a well-fashioned, eternal spoon.

After all, a perfect spoon is hard to come by. Many chefs will acclaim the Kunz (pronounced ‘koonz’) spoon, named after recently deceased chef Gray Kunz. Honestly you cannot go wrong with this choice: its mirroring steel, that level lip with its deep bowl. Its perfect weight and balance. The subtle curve of its neck to your palm. In the kitchen hives it’s hard to find a spoon of equal charm. The Michelin-grade queen bees cannot deny its utter extravagance, and the worker drones cannot deny its usefulness.

But to be clear it is not all bedazzlement and stardom in the spoon-osphere: utility is king, beginning and end. And thus a prepared cook does not merely have a spoon: he has a set, three or four pieces that he has collected across years of searching, and tested with the fires of many kitchens. The Kunz is an ideal first choice, but the next spoon is the true workhorse of of the realm: the slotted spoon. If she is not ladling soups or plating sauces, the slotted is the only spoon a cook may need, the first choice in the hypothetical desert island scenario. Fortunately most cooks are not forced into a sandy exile where they can bring only one item of silverware, but it is good to have your priorities straight.

(Notice above that I did say ‘silverware’. The term is antiquated, but its alternative, ‘flatware’, is absolutely demeaning and not to be used here. The best you can wish for in a spoon is that its neck is long and its bowl is deep. The use case for a flat spoon is to buy in bulk and lend to your friends, sidestepping the worry of potential loss. A misplaced spoon is a tragedy; do not risk it.)

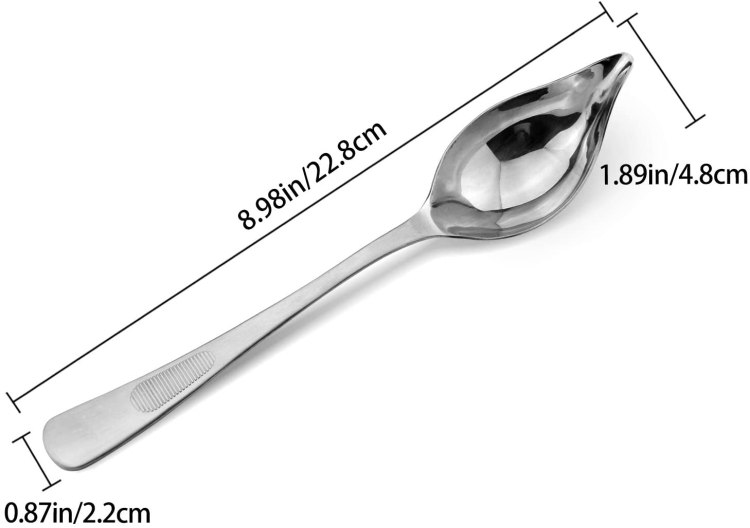

Beyond the solid Kunz and the slotted, options begin to open up. Your use case will vary. Some cooks need something large and durable, perhaps a basting spoon punched from fifteen-gauge steel sheets. Others may want something small, an ornate tasting spoon that only just fits your deli cup of beef jus. But in equal parts with function, the third spoon is also about style. A rosey bronze spoon can stand out from the stainless steel, but what about matte black? The history of an antique sterling spoon is captivating, but what of a silicone spoon for use on Teflon? Perhaps an extra-long J.B. Prince, or a teardrop-shaped Mercer? Self-exploration may sound a little indulgent when we are talking about chef tools… But there is a journey to be had, and when it comes to the art of stirring and pouring chefs are just as pretentious as bloggers and critics.

My personal third is a saucier, deep-bowled with a thin tip for pouring. It is a glorious tool, though for me largely just an excuse for showing off. If I were to be cruel, I would say that it tends to be too single-focused, the thorn in my utilitarian paw. Akin to a garlic press, it is a tool I require at most twice a night, and shun otherwise. But it is my third, and I use it well…

… Ultimately this should not have been my third. What I wanted, what I needed for my third was a quenelle spoon, to assist in forming that perfect football of sorbet or whipped cream. Some would avow skepticism that I do not prefer Kunz for the one-handed quenelle. But no, I have fever dreams of my perfect quenelle spoon, fixations the Kunz simply cannot cut.

In my time I have discovered only a few spoons that fully ingratiated these whims, and as quickly as I found them they were gone, forgotten in the knife bags of other cooks or thrown into the steel belly of an industrial dishwasher, a sacrifice to the kitchen gods. I was foolish not to cling to these immaculate wonders for the treasures they were, and now they are only sad memories, persistent but slowly fading.

The loss of a perfect spoon is a great tragedy. But I might also argue, that perhaps loss is just a part of the journey. And so I continue in my art of stirring and pouring, clinging to my faithful tools and eagerly awaiting the arrival of my perfect third.